Global Britain: The Confidence to Lead

At CGP, our default position is one of optimism about the prospects for a better world and the distinct, important role that the UK can play in helping to bring that about. As the UK has shown in Ukraine, the UK can accomplish remarkable things when its goals are clear, its commitment sustained and when it works pragmatically in partnership with its allies. We want to see the UK apply the same level of ambition and self-belief in addressing many of the challenges that will define the decades to come.

In an age of heightened geopolitical tension, we want to ensure that the UK has the structures and resources in place to respond to some of the longer-term threats and opportunities that it will face. In the wake of the Integrated Review, and the FCDO’s more recent International Development Strategy (IDS), now is a good time for that reflection.

We regard the ambition set out in those documents as the right approach, but we think that there is more that the UK could do to maximise its influence in the world and further a vision of world order that is more in line with its preferences.

In a contest of ideas and values, we do not doubt that when people are given a choice, they will opt for freedom and prosperity. Yet a common thread in British politics today seems to be a kind of pervasive fatalism. A belief that sustained economic growth is somehow unrealistic. A belief that China’s growing influence cannot be checked or countered. It chimes with a powerful groundswell of pessimism amongst much of the British public, who struggle to believe that a positive vision of the future is possible.

There certainly are countries whose vision of the future differs starkly from our own. This is particularly true in the case of China, which has genuine assets that it deploys in pursuit of its own strategic goals. We should not lose sight of the fact that it often fails in this endeavour, alienating its potential partners in the process and damaging its global standing. That should give us confidence that there is scope for an alternative; that the building of alliances is possible, whether ‘networks of liberty’ or more ad-hoc coalitions of mutual interest.

The UK will struggle to win this longer-term exercise in persuasion if we do not dedicate the resources and attention needed to do so: we should be thinking now about the world in 2050, not just in 2030.

This report will set out some of the practical steps that we think the UK should be taking with that longer-term perspective in mind. It will explain why we should be confident in that distinct, positive role the UK could play, but not assume that it can take on that role blithely or take the challenge that it represents unseriously.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1: The Government should build on its recent decision to create a new Minister for Development attending Cabinet by making this a joining HMT-FCDO role, to ensure coherence across government. This should complement the current arrangements in place for broader co-ordination of UK foreign policy.

Recommendation 3: Instead of pitting the defence, development and diplomacy aspects of the Government’s work against each other and compromising all three of these things, the Government should use the opportunity of a new Spending Review to revisit the level of resourcing to the UK’s foreign policy.

Recommendation 5: The Government should also set out clearer, transparent rules about how more flexible funding can be accessed to address huge, unanticipated costs without derailing any longer term commitments that the UK has made.

Recommendation 7: As part of the new cross-government China strategy, the Government should set out a plan for managing the risk of fragmentation among partners, with particular reference to the ways in which the international system can help mitigate this risk.

Recommendation 2: The Government should create a new Forum on UK-Africa co-operation, which builds on the African Investment Summit. This should become a regular, biannual fixture, as a signal of the UK’s willingness to invest ministerial time into cultivating longer term partnerships in Africa. It should become broader in scope, to allow for discussion of the full range of issues, including security co-operation, trade and not exclusively on investment.

Recommendation 4: The hard cap of 0.5% ODA spending should be eased, to create better incentives for the UK to be able to act as a force for good in the world. HMT should explore a new funding formula, with a core budget less exposed to the significant displacement risks that are bad for the FCDO’s longer-term priorities and partners.

Recommendation 6: Core funding for the FCDO’s diplomatic needs should be addressed as part of this and appropriate funding for the diplomatic network secured.

Report Polling: Headlines

In the soft power contest in areas of significant geopolitical competition, the UK is winning.

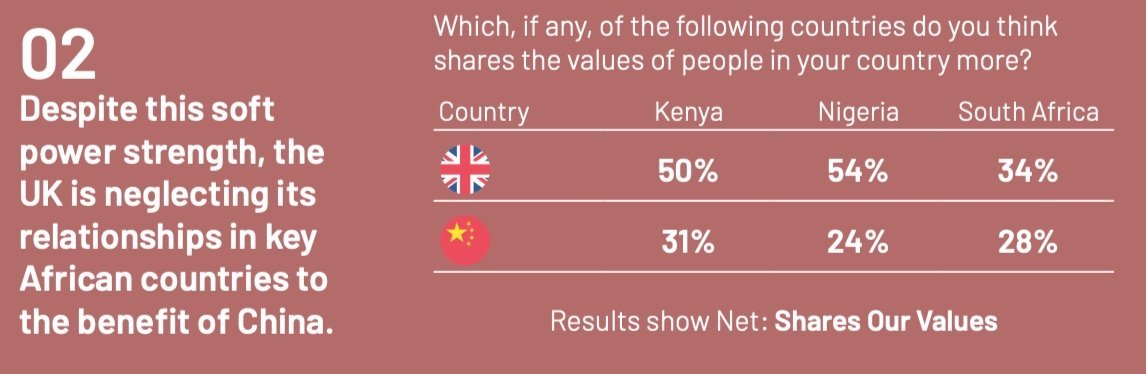

Despite this soft power strength, the UK is neglecting its relationships in key African countries to the benefit of China.

The UK remains the most trusted partner in foreign policy according to the US public.

There are important questions about the skills, resourcing and structures that the government should have in place if it wants to maximise its global impact. These are addressed more fully in the second part of this report. But the perceptions that people have of this country matter too and have a significant impact on the kind of global role that the UK can realistically play in the future. Again, we think that it is worth reflecting on the extent to which these perceptions about the UK tend to be positive and again suggest that there is ample scope for the UK to play a significant global role.

For this report, we conducted polling in two stages and of two different audiences with the aim of finding out how the UK was perceived on the world stage and also by checking how optimistic respondents were about the future of their country. First, using a sample of 1300 adults across the United States we polled adults from a representative mix of gender, age, race and political backgrounds. We first asked about the optimism they felt about the future of their country. The next questions looked at how dependable they saw other G7 allies on the world stage. The UK was ranked against Japan, Germany, France, Canada and Italy on areas of how reliable they felt each country was and which country they see as most committed to standing up for democratic values.

The second phase of the polling focused on three African nations - Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa - where we polled a representative sample of gender and age group. Again, we began with asking about optimism about the future of their country. In this poll, we then asked respondents how much attention they felt the UK, US and China pay to the priorities and interests of their country and the wider region. Following this, we then asked how much importance they felt the UK, US and China placed on the relationship with their country. Respondents were then asked whether they believed the United Kingdom or China shared the values of their country more before asking which country they saw as being more committed to standing up for democratic values out of the G7 and China.

Global Britain: The Confidence to Lead was launched in Westminster Abbey by the Rt Hon Dr Liam Fox MP, Former Secretary of State for International Trade and Secretary of State for Defence.